Thursday, December 21, 2006

Merry Mazel Tov: SNA fun for the whole family

It's a pretty good exam, which makes the grading tolerable. If you're bored this Christmas weekend, give it to your kids and let the fun begin!

Thanks also to Simon Clay Michael for teaching me the handy phrase "Merry Mazel Tov."

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.5 License and is copyrighted (c) 2006 by Connective Associates except where otherwise noted.

Tuesday, December 19, 2006

Net Gains: handbook by Plastrik and Taylor

Net Gains

A Handbook for Network Builders

Seeking Social Change

By Peter Plastrik and Madeleine Taylor

—Sponsored by the Wendling Foundation—

From the INTRODUCTION to NET GAINS

It is intended to join, complement, and spur other efforts to capture and make widely available what is being learned in the business, government, and civil sectors about why and how to use networks, rather than solitary organizations, to generate large-scale impact.

We start with the point of view that networks provide social-change agents with a fundamentally distinct and remarkably promising “organizing principle” to use to achieve ambitious goals. Given the complexity and enormity of social problems, the unrelenting pressure to reduce the cost of creating and implementing solutions, and the recent proliferation of small nonprofit organizations, networks offer a way to weave together or create capacities that get better leverage, performance, and results.

Relying on networks to generate social change is not new to philanthropy and nonprofits. Many foundations have funded the civil rights, feminist, and consumer movements for decades and more recently have assembled “learning networks” of grantees that work together to innovate and improve their practices. As Jon Pratt, executive director of the Minnesota Council of Nonprofits, points out, “community organizers and grass roots organizations have applied network concepts for years.”

But something new and important is afoot. The nonprofit and philanthropic sectors are under growing demand to do more and to do better. The number of nonprofit organizations is expanding substantially, as are the tasks the civil sector undertakes in light of government downsizing. “We’re seeing growth of nonprofit organizations, but not much change in the systems they are trying to impact,” says Pat Brandes, a foundation executive in

Foundations, a crucial capital market for nonprofits, and governments that contract with nonprofits increasingly seek improved impact, leverage, and “return on investment.” Nonprofits are routinely expected to be more strategic, entrepreneurial, and “high performing,” and to focus on producing outcomes. Some efforts to increase the impact of nonprofits, such as “venture philanthropy,” have focused on strengthening individual organizations to be more effective and efficient. But, as the Maine Community Foundation notes, this approach can be inefficient, since its capacity-building resources are invested across many organizations without regard for redundancy and overlap among the organizations. Meanwhile, foundations typically fund programs rather than methods of delivery, but more of them are forming their own networks, rather than going it alone, to develop their strategies and pool their resources.

In this shifting context for the civil sector, networks represent a fundamentally different response to achieve efficiency and effectiveness. They should not be dismissed as merely the latest fad promoted by business leaders, consultants, and foundations who don’t understand the uniqueness of the nonprofit world. “Network strategies offer a powerful set of tools to manage the key tasks and challenges faced by nonprofits,” argues Jon Pratt. “Network thinking offers powerful analytic and strategic tools for nonprofit boards and managers to increase the stability, influence and autonomy of their organizations.”

Most of us have networking in our blood. We build personal networks and connect with other individuals or organizations to get things done that we can’t do by ourselves. But there’s much more to network building than this instinct to link. Building a network is a practice about which much has been learned from the experiences of network builders themselves and the experiments and insights of researchers in mathematics, physics, anthropology, and other disciplines.

This is news to most of the social entrepreneur-network builders we meet. Networks in the nonprofit sector are rarely organized to take full advantage of what networks can do. “We in the nonprofit sector always say, ‘We connect,’ but we don’t really know much about connecting,” observes Marion Kane, executive director of the Barr Foundation.

For many decades, the overriding organizing principle of the social-change sector, as with business and government, has been the stand-alone organization. This focus has driven the understanding of management and leadership; the CEO or Executive Director at the helm of the lone organization has been an icon of the age. But hierarchical, organization-centric is losing its sway. Many people, even in the largest, most venerable organizations, recognize now that to gain greater impact they have to let go of organization-centric ideas about how the world works, and they are adopting network-centric thinking.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Introduction

The Authors

Acknowledgments

Part I: Is a Network Approach Right for You?

1. Starting Points 11

2. What We Mean by Network 14

3. The Difference a Network Makes 18

4. The Business Case for Social-Change Networks 24

5. Gut Check: What It Takes to Build Networks 28

Part II: Organizing Networks: Seven Decisions

6. Three Networks in One: Connection, Alignment, and Production Nets 33

7. Reasons that Bind: Collective Value Propositions 39

8. Who’s In, Who’s Out: The Privilege of Membership 45

9. Who Decides What and How: Network Governance 48

10. The Shape of Things To Come: Structures of Networks 51

11. Rules to Live By: Operating Principles for Network Building 58

12. The Different Roles of Network Builders 61

13. When Funders Organize Networks 64

Part III: Managing a Network’s Development: Five Tasks

14. Weaving Connections: Ties that Bind 68

15. Facilitating Alignment: Production Agreements 74

16. Coordinating Production: Who Does What 78

17. Operating the Network: Management Issues to Anticipate 81

18. Taking a Network’s Pulse: Monitoring and Evaluation 87

19. Visualizing Networks: Maps that Reveal 97

Part IV: Net Gains in the Social-Change Sector

20. Building the Civil Sector’s Networks: Five Strategies 102

A Network Glossary 107

Resources for Network Builders 109

End Notes

The Authors

Wednesday, December 13, 2006

Promote cooperation with both carrots and sticks

How much would you invest in such a fund? The answer clearly depends on how much everyone else is going to invest. Can you trust your co-investors to put in at least as much as you do?

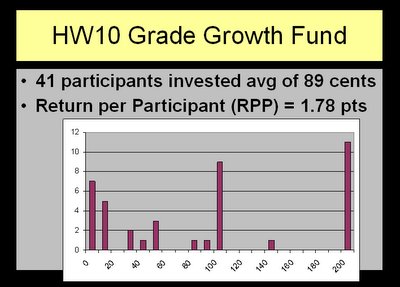

A few weeks ago I invited my students to participate in this experiment by investing their hard-earned grade points in exactly such a fund, as a homework exercise (HW10, to be exact). To protect against individual ruin, I limited the maximum investment to 2 points out of 150 earned over the course of the semester. By requesting deposits in "cents" (0.01 of a point), I gave students a range of 0-200 to choose from.

Here are the results. You can see that many students chose to invest 200 cents (the maximum allowed) but there were enough free-riders in the fund so that even after doubling, the fund returned less than 200 cents to each investor.

In other words, many students lost 0.22 points by investing in the fund.

In other words, many students lost 0.22 points by investing in the fund.Claire Reinelt alerted me yesterday to German researchers B. Rockenbach and M. Milinski, who did a very similar study and got their results published in Nature just this week. Their study also allowed fund investors to dedicate a portion of their deposit to punishing free-riders on the fund. This option turns out to be a critical ingredient to designing a fund with maximal collective gain. See also this cute Boston Globe article on the study: "Want cooperation? Carrots and sticks get the best results."

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.5 License and is copyrighted (c) 2006 by Connective Associates except where otherwise noted.

Tuesday, December 12, 2006

BU students ponder the Internet and social epidemics

Their last homework assignment was writing a short essay on how the Internet affects social epidemics in America. During the semester we explored this question in many ways--by blogging and programming with HTML and JavaScript, by studying the mathematics of information diffusion and economic externalities, and by experiencing social epidemics within our own classroom (of 62 students) and reflecting.

The following two student essays do a great job of digesting the material of the semester and addressing the question, "does the Internet make future social epidemics more or less likely?"

- Those of you who wonder why such a question is even worth asking should start with this essay on how the Internet limits epidemics, written by Drew Phillips '09;

- Here is an excellent essay on how the Internet increases epidemics, written by A Garrett Robertson.